By Sara Raquel Roschdi

On June 6-7, 2025, the UCLA Labor Center gathered advocates, scholars, and organizers in Los Angeles to discuss the impacts of the H-2A guest worker program on the working conditions of farmworkers on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. This binational convening focused on exploring strategies to support migrant agricultural workers and push back against the labor exploitation built into the H-2A guest worker visa program.

Understanding the Mexican Context

The H-2A visa program, designed to supply temporary agricultural labor to the U.S., heavily relies on recruitment in Mexico, with San Quintín, Baja California, emerging as a key training ground for workers before they enter the U.S. labor system. Dr. Rubén Hernández-León opened the conference by sharing his research findings, noting that many migrants from states such as Guerrero, Michoacán, Guanajuato, and Jalisco travel to San Quintín with the hope of eventually obtaining an H-2A visa. Guatemalan workers are also increasingly funneled into this process. Despite its importance, there is a significant lack of data on the precise geographic origins of H-2A workers.

A striking insight into the power dynamics of this migration is reflected in how workers describe their journey. The convening participants reflected on how many of the H2A workers they organize alongside say, “They took me,” rather than, “We came,” revealing a profound sense of coercion and lack of agency from the very beginning. Once enrolled in the program, workers quickly confront harsh economic realities—wages often fail to cover even basic living expenses. As Lorenzo Rodríguez of Sindicato Independiente Nacional Democrático de Jornaleros Agrícolas (SINDJA) explained, “Cuando se dan cuenta que la canasta básica está por las nubes, se dan cuenta que lo que les están pagando tampoco les alcanza” (“When they realize the cost of basic goods is sky-high, they also realize what they’re being paid isn’t enough”).

Recruitment firms and agribusinesses play central roles in managing this flow of labor under the H-2A program. However, as Lucas Benítez of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) warned, “Antes había esclavos; ahora se ‘alquilan’ trabajadores” (“There used to be slaves; now workers are ‘rented’”), highlighting how the H-2A program commodifies and exploits migrant labor under a modern guise.

Challenges to Effective Oversight of the H-2A Visa Program

Marcos López of the UC Davis Labor and Community Center explained that the H-2A visa program suffers from inadequate oversight, a problem that spans from recruitment practices in Mexico to working conditions in the United States. He emphasized the lack of accountability in the system, noting: “Farmworkers holding H-2A visas face a variety of systemic abuses such as being unable to act on their rights regarding workplace and housing protections,” highlighting how broken promises continue to undermine worker protections.

Sarait Martínez and Yesica Guzmán from Centro Binacional para el Desarrollo Indígena Oaxaqueño (CBDIO) called for laws mandating the formal registration of recruiters. They raised concerns over the lack of state oversight, citing chronic understaffing at key agencies like California’s Employment Development Department (EDD), which is responsible for monitoring employer compliance with H-2A recruitment and hiring practices, and the Department of Industrial Relations (DIR), which enforces labor standards and workplace protections for farmworkers. Martínez warned, “There are only three inspectors in the entire state responsible for monitoring an estimated 42,000 H-2A workers, and California’s budget cuts threaten to widen this gap even further.” These regulatory gaps raise concerns about increased violations of labor protections and the lack of mechanisms to hold employers accountable.

Organizers across the attending organizations shared the need to build unity between local and H-2A workers. Juvenal Solano of MICOP warned, “Se usan amenazas de reemplazo por H-2A para frenar huelgas” (“Threats of replacing local workers with H-2A workers are used to stop strikes”), exposing how employers weaponize the program to undermine collective action. Similarly, Martínez shared an example: “Algunos empleadores traen a los trabajadores H-2A los fines de semana para evitar pagar horas extras” (“Some employers bring H-2A workers in on weekends to avoid paying overtime”), illustrating how such practices increase competition for hours among farmworkers already struggling to survive on low wages.

While NGOs have documented that housing provided independently from employers can safeguard worker autonomy, exploitation remains rampant. Erica Díaz from CAUSE further condemned policy rollbacks that have worsened living conditions: “Se modificaron políticas para permitir viviendas en zonas remotas sin servicios” (“Policies were changed to allow housing in remote areas without basic services”), further isolating workers from public service and regulatory oversight. As Inî Mendoza from Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales (FIOB) starkly described, “Las compañías hacen lo que quieran con los trabajadores. Cuando nosotros terminamos, ellos todavía están trabajando” (“The companies do whatever they want with the workers. When we finish, they’re still working”), revealing the excessive workloads and unchecked control employers hold over H-2A visa workers.

Policy, Advocacy, and Resistance

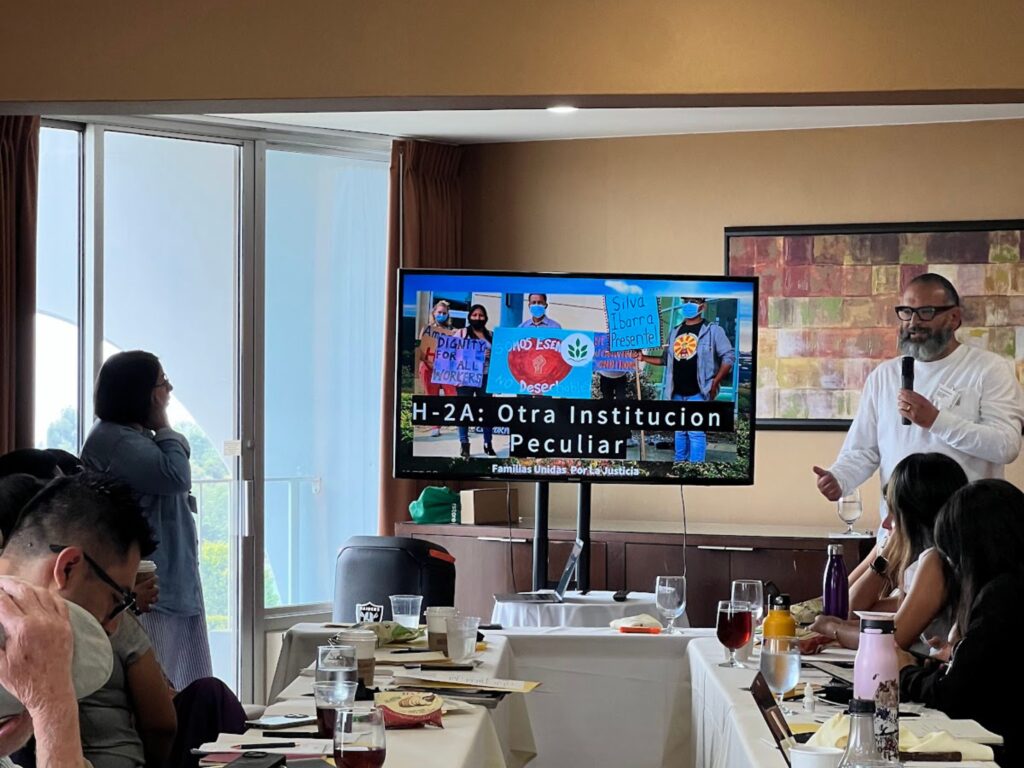

In Washington State, Edgar Franks of Familias Unidas por la Justicia (FUJ) spoke about the organization’s efforts to push for the creation of a tripartite H-2A committee made up of workers, employers, and state agencies. Franks shares that the H-2A Oversight Committee was ultimately established in response to the lack of sufficient oversight “at the local, state, or federal level.” Thanks to advocacy led by FUJ and allied groups, legislation was passed to form the committee, which includes four farmworker representatives, four industry or rancher representatives, and four state officials from agencies such as the Employment Security Department (ESD), Labor & Industries (L&I), and the Department of Health. These efforts not only address immediate gaps in accountability, but also lay the foundation for potential H-2A oversight structures in other states across the country.

Meanwhile, in Florida, Lucas Benítez of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) highlighted the power of the CIW’s “Fair Food” model, which leverages market pressure on major buyers like Taco Bell to enforce basic labor standards. Their demands are straightforward but essential: clean drinking water, access to restrooms, and fair wages. Benítez shared that they are simultaneously advancing campaigns that go a step further, aligning with the broader goal of farmworker organizations across the country to “igualar salarios y derechos entre locales y trabajadores huéspedes” (“equalize wages and rights between local and guest workers”).

At the national level, journalist and activist David Bacon traced a broader rollback of protections targeting farmworkers. He exposed how, under the Trump administration, “Trump propuso congelar salarios y eliminar protecciones H-2A, lo que podría resultar en el despido de un millón de trabajadores, principalmente del campo” (“Trump proposed freezing wages and eliminating H-2A protections, which could result in a million workers—mostly farmworkers—being laid off”). Today, less overt tactics, such as tax audits and regulatory loopholes, continue to intimidate workers and suppress organizing efforts.

Toward a Binational Agenda for Justice

The gathering concluded with focused working groups advancing a shared vision grounded in public policy, worker organizing, and applied research. Participants expressed an urgency for legal reforms to enforce strict oversight and mandatory registration of H-2A recruiters. They highlight the need for a significant investment in dignified, independent housing that protects worker autonomy, alongside support systems to build solidarity between local and H-2A workers.

Building on proven models like the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) and Familias Unidas Por La Justicia (FUJ), attendees emphasized the need to replicate successful monitoring and enforcement strategies. They also advocated for equitable visa and residency pathways that recognize and protect the rights of existing workers.

The binational convening concluded with a shared commitment to address the deeply entrenched injustices within the H-2A program and amplify the voices of the migrant farmworkers who sustain our food systems across both sides of the border.